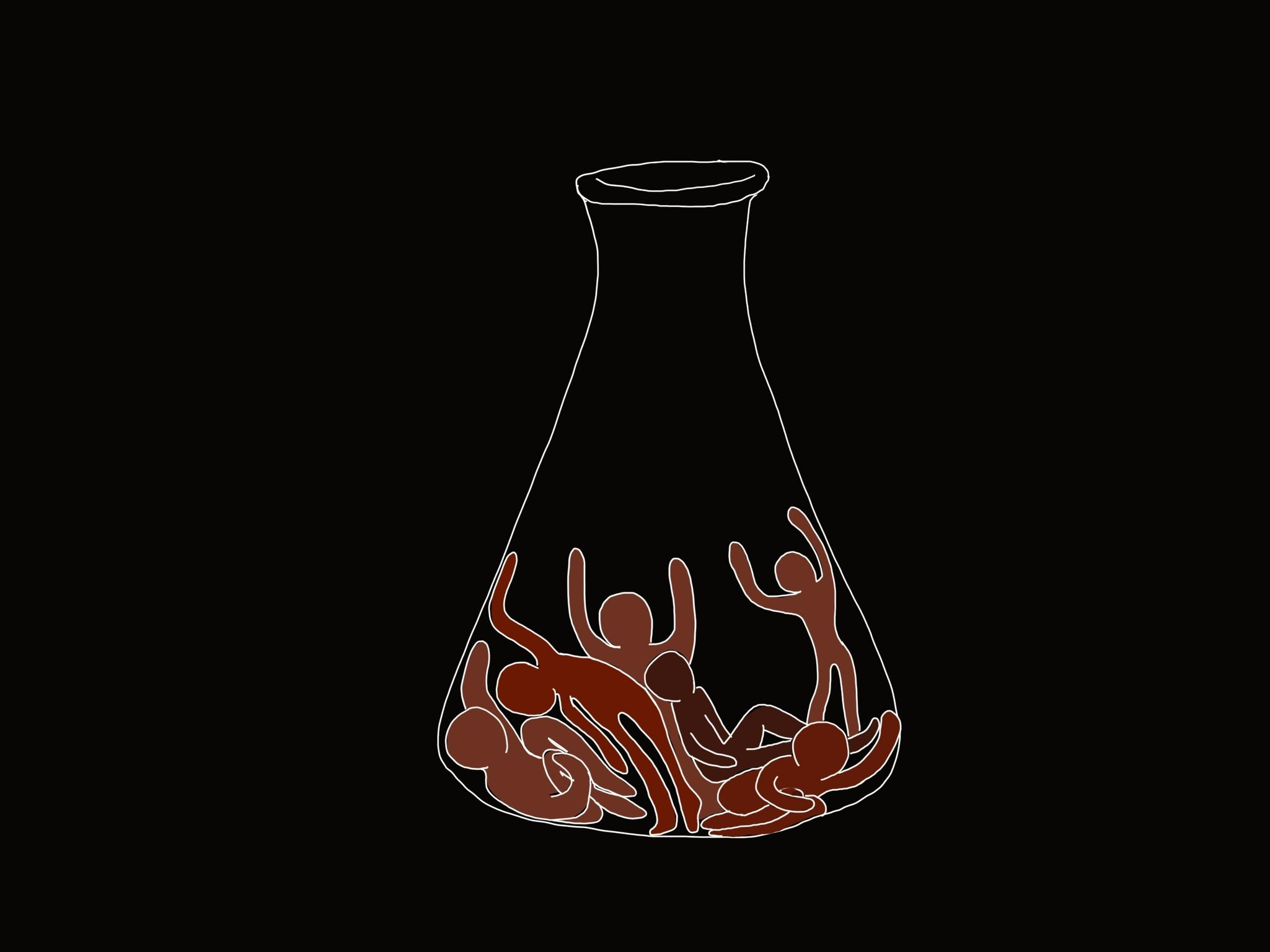

All great medical advances owe some degree of their success to sacrifice. Donated organs give us a better understanding of our body’s processes, clinical trials for treatments require human test subjects and surgery would never have been created without someone putting their life on the line in the name of science. As risky as they can be, experiments are a prerequisite for progress.

However, these discoveries are often riddled with questionable conduct by the researchers, and over the years, people of color have been disproportionately affected by inhumane experiments. James Marion Sims, who is known as the father of gynecology, developed techniques for surgery by operating on enslaved women. He refused to use anesthesia, claiming that African Americans could not feel pain.

Richard Pearson Strong, a Harvard University professor and researcher, traveled to the Philippines in 1906 to study the effects of tropical diseases. He injected 24 prisoners with a cholera vaccine without their consent. However, the vaccines had been contaminated with traces of the Bubonic Plague, and 13 of the men died.

In 1932, the government began a now-infamous experiment known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Nearly 600 African American men applied to a government-funded program that promised treatment for “bad blood,” a blanket term for rheumatism and a variety of other conditions. The majority of the men were poor, with no access to healthcare, and in return for their participation they were offered free meals, physicals and burial insurance.

Of the 600 men in the study, 399 were diagnosed with syphilis. However, the doctors never revealed this diagnosis to the patients, denying them treatment in order to study the effects of the disease. The doctors not only refused to treat their patients even after a cure was discovered, but they actively prevented patients from seeking care elsewhere. The experiment lasted from 1932 until 1972, and resulted in at least 128 deaths. At least 40 wives were also infected, and 19 children were born with the disease. It took the U.S. government until 1997 to apologize for the 40-year study.

Henrietta Lacks, an African American cancer patient whose cells were taken, reproduced and experimented on without her knowledge or consent, died a poor tobacco farmer in 1951. Her cells were replicated trillions of times, and helped develop the polio vaccine, gene mapping and chemotherapy. In fact, her cells are still widely used by research institutions to this day. However, her family was never compensated, and consequently remained poor, often struggling to access the very treatments that Henrietta’s cells made possible.

These discoveries are often riddled with questionable conduct by the researchers, and over the years, people of color have been disproportionately affected by inhumane experiments.

Stories like these are the reason that explicit, informed consent is imperative for conducting research ethically. Too often researchers have exploited the ignorance, poverty and blind trust of patients in the name of science. Despite the good that has come from these discoveries, the repercussions of unethical research practices can last for decades. The Tuskegee story, for example, led the African American community to use the health care system at much lower rates than before out of distrust of doctors. This contributed to a disparity in health and mortality rates between African Americans and Caucasians that remains to this day.

We’ve come very far as a country in terms of race and race relations, but stories like these remind us how very far we still have to go. Even in modern times, the lives of people of color are regarded as less valuable than the lives of Caucasians. It becomes apparent in routine traffic stops of law-abiding citizens that end in gunshots. We see it in the disparity between hurricane relief efforts in Houston and Puerto Rico. We can hear it when the President of the United States tells the world that he would prefer immigrants from Scandinavia over those from Africa. And we are reminded once again when we hear people ask why we still need to honor the history of America’s nonwhite citizens.

Understanding what it’s like to live as a person of color in America means confronting certain ugly truths about our country’s history. And the first step in embracing our country’s identity as a multicultural and multiethnic haven is to recognize the mistakes and wrongdoing of our past and aim to amend them.

Art by Hana Morita