It’s 1979 in Los Angeles. You wake up in a quiet house, in a foreign land with an unfamiliar language. You take the bus, you buy groceries, alone. Your parents? A mere 7,000 miles away.

This was the everyday life of my mother when she came to the US with her brother at the age of 13, from Hong Kong.

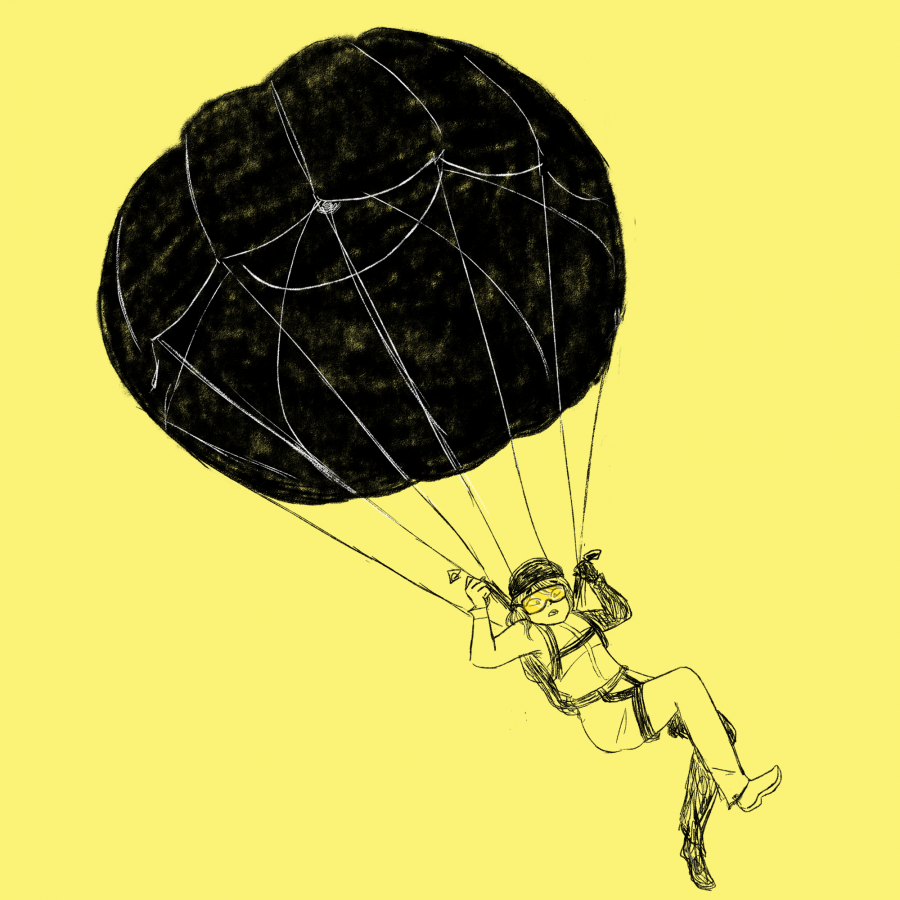

“Parachute kids” such as my mom, are kids who have been dropped off in a foreign country while their parents stay in the home country.

This phenomenon is far from dying out. In fact, the number of parachute kids only continues to grow. It is especially relevant to the Chinese community and California, as a quarter of these parachute kids land in either Los Angeles or the Bay Area.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the number of Chinese students in American middle and high schools has skyrocketed from 1,200 to 52,000 in the past decade, the percentage of Asians in Palo Alto High School alone went up from 27% to 37%.

Although the reasons for becoming a parachute kid differ, a majority of them come in pursuit of the American education system, and hopefully a diploma from one of America’s top universities as reported by the New York Times and the South Morning China Post.

As to be expected when children are left without their parents in a new environment, there is a sense of melancholy that not even a degree from a prestigious school could heal. My mother, a proud UCLA graduate can attest to that.

Even though interviewing a relative for a feature goes against Journalism norms, I knew that my mom, as an ex-parachute kid, would have an intimate perspective on the issue.

“It [was] pretty quiet at home.” my mom, Marian, told me.

Not scary, but quiet. I just want to be with people.

-Marian Seah

“Not scary, but quiet. I just want to be with people. If not then I’ll turn on the TV so there is sound.” This deafening silence was a constant reminder of vulnerability.

“There’s no moral guidance. You see some of your friends trying to join gangs and you try not to do that. You try to find teachers or church counselors to guide what is right was wrong.”

My mom’s unique experience of being a parachute kid had altered her life and continues to do so.

“I lost that childhood that you’re supposed to have and that closeness that with your parents.” She says.

Not all of the damages of neglection were mental. Because of the need to belong and the need for guidance, my mom said that falling into substance abuse and crime were all too common.

“One of my friend’s parents owned a dry cleaning shop in Hong Kong. They could only come for half a year at a time, the other half they were not home. The brother got involved in drugs, alcohol, and also a lot of parties and a lot of gang recruitment,” she says.

Despite all of the turmoil around her and within herself, my mom claims the experience did offer some benefits. She was lucky to have landed in an area with many other parachute kids, and they were able to create a community in the Chinese-speaking church.

“We had a community of Mandarin and Cantonese-[speaking] people. There were a lot of them so we would gather with all the immigrants so you don’t feel so isolated in language,” she says.

“We learned how to cook rice, clean dishes, boil water and we did homework together. We would hang out in the restaurant eating french fries, and we talked and we talked and talked until like maybe 4 a.m. Then, we’ll go to school at 7 a.m.”

My mom is still close to her friends today, 30 years later.

A lot has changed since my mom came to America.

Current day parachute kids have access to apps that make it easier to stay in touch with family, and video tutorials that could help kids learn how to be independent.

Nowadays, most parachute kids stay with a friend of a family, or if they aren’t so lucky, a stranger from the internet paid $1,000 a month to house the kid, as reported by the Los Angeles Times.

My mom says, however, that there are some aspects of the experience that still endure today.

“Parents want their kids to have a better future, but they neglected the psychological and mental development of the kids who are forced to assimilate into a foreign culture with no connections, [who are] relying on strangers or acquaintances,” says Seah.

“Not all kids can survive. It’s painful to feel like you are neglected at such an early age. That vulnerability will affect your whole life.” She says.

“Like how to rely on yourself and your self-confidence. Especially if you are here illegally, there’s a lot of things that you cannot share with other people and that’s a lot of stress for kids.”

When asked if it was all worth it, her answer was honest. She doesn’t know if her life would be better or worse if she stayed in Hong Kong.

However, she is certain of the impacts of the experience on her life and on the lives of the next generation of parachute kids.