On Wednesday, February 22, Srinivas Kuchibhotla and Alok Madasani, both engineers and immigrants from India, were at a bar in Olathe, Kansas. A man, Adam Purinton, approached them, using racial slurs and other insults, including asking them what visas they used, whether they were legal residents of the United States and calling them terrorists. Other customers complained and he was eventually thrown out of the establishment. He returned with a gun, shouting the words “get out of my country” before opening fire. The shooting killed Kuchibhotla and injured many others, including Madasani. Purinton fled to another bar 70 miles away and told employees of the bar that he was on the run, having just killed “two Middle Eastern men.”

Sean Spicer, Press Secretary of the White House, insisted that there was no correlation between President Trump’s immigration policies and the shooting, dismissing the notion as “absurd,” despite the fact that Islamophobia in the United States has reached its highest point since 9/11; despite the fact that barring Muslims from entering this country was one of Trump’s signature campaign promises; despite the fact that Trump has claimed “Islam hates us,” in an interview with CNN; despite the fact that he allegedly saw “thousands” of Muslims celebrating the terrorist attack on the twin towers.

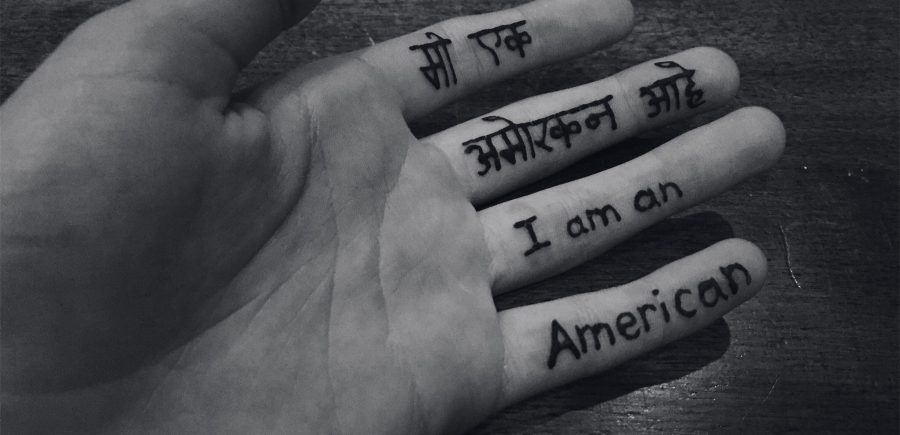

As a proud granddaughter of Indian immigrants, I’m saying that enough is enough. This needs to stop. It is time for Trump to realize that he can no longer act as though his words have no impact. The things he says have consequences, for every single American, because here’s the thing: Trump’s statements about fighting terrorism are not targeting the terrorists. Not even close. They are targeting Muslim Americans, ordinary people who have as much in common with members of ISIS as most Christians do with the KKK or the Westboro Baptist Church. But this hatred and racial profiling doesn’t just target Muslim Americans, it targets anyone and everyone who doesn’t look “American” enough. It targets everyone who looks even remotely Middle Eastern, including members of the the South Asian community. Growing up in a mixed race family, I saw examples of this prejudice and ignorance firsthand. I have been stopped for “random” security checks, questioned in security lines and overly scrutinized multiple times when traveling with my Indian mother and her family, but never once when traveling with my white father. The number of times people have asked me if I “speak Hindu” is frankly, a little ridiculous. As is the amount of people who have asked me what my “Indian name” is. (Still Maya, by the way.) I grew up hearing stories of the prejudice my relatives faced for being Indian American in predominantly white communities, so believe me when I say that this is not the first time that my people have been targeted simply for looking like the enemy.

We are still operating under the assumption that to be truly, one hundred percent American is to be white, and that any other coinciding identity must be accompanied by a hyphen or an asterisk.

Almost 3000 people died on September 11, 2001, but for many Americans, the danger lingered in the aftermath of the attack. Hate crimes against Muslims and those perceived as Muslims skyrocketed, from 28 reported attacks in 2000 to 481 in 2001. Four days after the attack, Balbir Singh Sodhi, a Sikh immigrant from India, was shot and killed outside the gas station that he owned in Mesa, Arizona. The man who shot him confessed to wanting to “kill a Muslim” as revenge for the terrorist attack, shouting “I am a patriot!” as he was arrested. Fifteen years later, anti-Islamic hate crimes in the United States are still happening at a rate five times higher than before 9/11.

Sikh men in particular have been targeted in these attacks. Sikhism, a religion founded in the Punjab region of India in the 15th century, forbids men from cutting their hair. Because of this, many Sikh men wear turbans (known as dastaars) both as a religious symbol and to keep their hair out of their face. However, their dastaars also make them targets for hate crimes, as they are often assumed to be Muslim, despite the fact that most Muslims in the U.S. do not wear turbans, and the Muslims that do wear turbans wear a very different style than those of Sikhs. The two are not interchangeable.

However, prejudice against the South Asian community began long before 9/11. The shooting of Srinivas Kuchibhotla and Alok Madasani happened just three days after the 94th anniversary of the United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind case, a unanimous Supreme Court decision that barred South Asians from becoming American citizens. Bhagat Singh Thind was an immigrant from India, who joined the U.S. army and fought for this country during World War I. However, at this period in history, only “white free men” were eligible to become naturalized citizens, and South Asians (referred to as Hindus regardless of their faith) were denied citizenship because although they were considered Caucasian, the Supreme Court decided that they could not be classified at “white” under the law. The ban was enacted in 1923 and remained in place for 23 years, until it was overturned in 1946.

Trump’s statements about fighting terrorism are not targeting the terrorists. Not even close. They are targeting Muslim Americans, ordinary people who have as much in common with members of ISIS as most Christians do with the KKK or the Westboro Baptist Church.

All of this circles back to one common thread: the idea that South Asians and Middle Easterners are not “American” enough to ever belong in this country. Even though this country would not have existed as it does today without immigrants from every part of the world, we are still operating under the assumption that to be truly, one hundred percent American is to be white, and that any other coinciding identity must be accompanied by a hyphen or an asterisk. It’s easy to forget that, excluding Native Americans, we all came from immigrant roots. This always has been and should always be a place for people to change their lives for the better, to claim opportunities they might not have been given elsewhere. My ancestors came to this country in search of a better life, just like yours did.

They are Indian, and they are just as American as everyone else.