1. A History of Food

The American pride, and yet simultaneously the evil, is encompassed in our food.

Over the span of human history, what we eat has consistently evolved. As primal humans, we discovered cooking, giving us an advantage over other species and allowing us to develop the complex societal structure we hold today. In times of war and hardship, we have scrapped and scavenged, in order to make it through yet another day. During the Industrial Revolution we introduced laws to regulate the safety of our food as it became increasingly more processed. Soon enough, food morphed into an American obsession; perhaps the American obsession. While food once was a necessity for life, we now entertain the ideas of diets and juice fasts. The American pride, and yet simultaneously the evil, is encompassed in our food.

Yet over the past half century, while we have been worrying about the nutritional benefits of our food and the physical effects of our food on our bodies, we have given little thought to how food impacts the world around us, namely the environment.

2. A Contemplation of Meat

I wanted to comprehend my nourishment.

This could be said for many other people: I’ve had a long and complex relationship with food. It was devoured at a young age, simply accepted in my elementary school years, and ignored but eaten in my middle school years. It wasn’t until high school that I began to seriously consider the impact of my food beyond satiating my hunger. I began to feel unsure about what I consumed, not for nutritional reasons, but because I didn’t want to aimlessly put food in my body: I wanted to have a deeper connection than that. Simply accepting the food that was keeping me alive wasn’t sufficient, I wanted to comprehend my nourishment.

It began with a deep contemplation of every dish. I’d imagine where my apple came from. Where was it grown? Whose hands had harvested it from the tree? How far did this apple travel to reach my hand?

As much as I contemplated the vegetables and fruit and bread I consumed, I contemplated the lives of the animals I ate many times more. I wanted to know when the animal had been born and when it had died. Who had raised it? Did it live a good life? But most importantly, I could not begin to fathom the volume of resources that had been funneled into the growth of this animal as it was raised for slaughter. Up to this point, I had never pondered the peculiarity of raising animals in masses with the sole intention of eating them.

I’d bite into a piece of chicken and I’d feel the fibrous muscles of what was once a bird being slashed by my teeth. I’d think of the blood that once pulsed through the pale veins, now exposed and dangling from the limp wing. I’d see the carmine blood dripping from the charred steak, evoking the image of a slaughter house, with the sliced cows limply hung from a rack. I’d slurp and chow on the dumplings and examine the curiously greasy ball composed of bits of dubious pork.

It was here that it began: my trials and tribulations with the animals I consumed.

3. A Statistical Compilation of Meat Consumption

Just like every other industry, meat production is designed to churn out as much money as possible, with little regard to the environmental ramifications.

Americans consume an astonishing amount of meat per capita. In 2015, only 3 countries―Paraguay, Argentina, and Uruguay―consumed more meat per capita than the U.S. according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). While the amount of meat consumed per capita changes each year (some years, Australians consume the most meat), different sources present varying findings, and results fluctuate depending on the definition of meat (whether or not seafood is included), the U.S. is consistently placed as one of the top consumers.

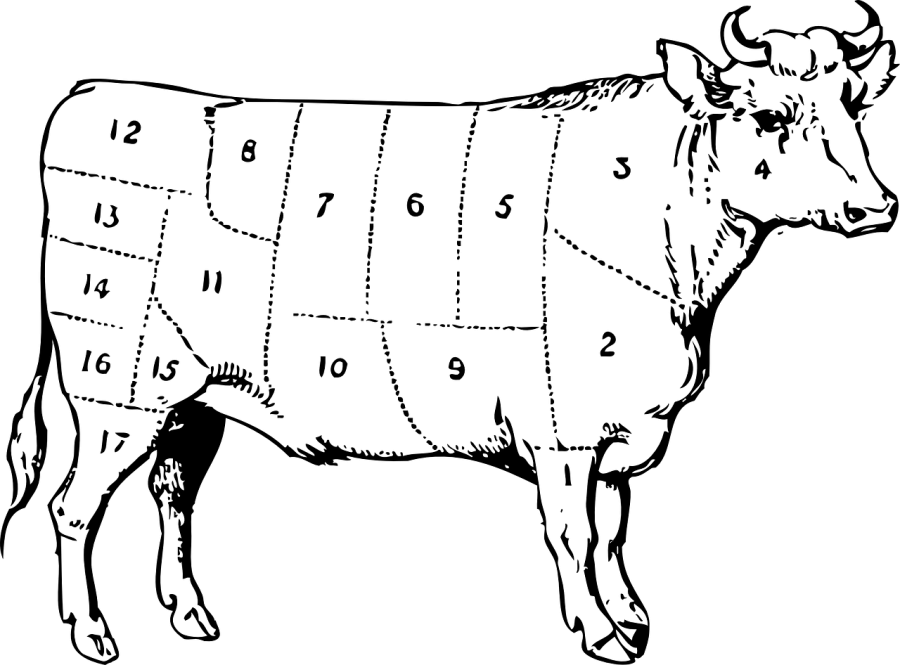

The average American consumed an astounding 210 pounds of beef, poultry, pork, and sheep in 2015; the equivalent of eating one and a half pigs or half a cow (when only the weight of retail cuts are taken into consideration). Another way to think about it: we eat more than our own body weight in meat every year. The average American weighs only 181 pounds: the average American man being 196 pounds and the average woman being 166 pounds.

Numbers up until now spare the details relating to the amount of resources used to raise these animals for consumption. A plump and juicy hamburger may be the quintessential American dish, but also one of the largest depleters of natural resources when it comes to meat. To put it into perspective, a single quarter-pounder requires 6.7 pounds of feed, 52.8 gallons of water, 74.5 square feet of grazing land, and 1036 Btus of fossil fuel energy to make it from the fields, to the slaughterhouse, to the processing factory, to the florescent store, to your refrigerator, to the sizzling grill, to the plate in front of you, and into your stomach. The amount of methane emissions produced by the cow are yet to be mentioned. Today’s industrially raised and slaughtered cows are not meant to be sustainable. If anything, just like every other industry, meat production is designed to churn out as much money as possible, with little regard to the environmental ramifications.

Natural resources may be one concern when it comes to the production of meat, but there is also an immense economic incentive to eat less meat. If every man, woman, and child in the United States simply followed federal dietary recommendations, which does not completely rule out meat, 197.1 billion dollars would be saved by 2050, after accounting for direct health care, indirect health care, and environmental savings. If every American went completely vegetarian, 258.6 billion dollars would be saved.

Often, the assumption is made that all vegetarians and vegans, or simply those who eat a reduced amount of meat, have made these dietary choices out of their love for animals, their overall dislike for the taste of meat, or for religious or health purposes; however, with the clock ticking down, flocks of environmentalists have joined forces with the meat-free community. The production and consumption of meat is one of the most unsustainable practices of our time, and yet it still remains a routine part of our diet.

4. A Disproof of Assumptions

Because the act of preparing and consuming food is such an intrinsic part of the human experience, those who diverge from food customs can be criticized.

The assumption that protein can only be found in meat is, as just stated, an assumption and nothing more. There is protein everywhere: beans, nuts, soy, dairy, eggs, oats, and certain seeds are all high in protein and equally delicious as meat when prepared correctly.

Additionally, some of the fittest people I know don’t eat meat, from vegetarian ultrarunners to vegan volleyball players. Plant-based diets do not obstruct one’s health. While, I do agree with divulging one’s desires and cravings every once in a while, the skills attained through learning to control these hankerings can transcend a diet.

The perception that vegetarians and vegans are all dreadlocked hippies donned with Chacos, tie-dye, and sun tea or a member of the coastal elite who can afford the time and money to think about their diet, can be found to be true, but as with all stereotypes, it can be disproved just as easily. Because the act of preparing and consuming food is such an intrinsic part of the human experience, those who diverge from food customs can be criticized. But we are just another group who break from the past’s broken habits; I, for one, see vegetarianism and veganism as a method to mitigate the irrevocable effects of climate change.

5. An Encouragement of Experimentation

I believe it is an ever-evolving journey, one in which I aspire to see eye-to-eye with my food.

There are, of course, ways to gain a better understanding of your meat without completely excluding it from your diet; vegetarians simply lie in the center of a spectrum stretching from carnivores to herbivores.

Firstly, don’t waste your food. This can apply to both plants and animals. By placing more food than we know we can consume onto our plates, we might be exercising the American ideal of abundance, but this practice is dually creating a surfeit of waste. By wasting excessive amounts of an animal, we are dishonoring, rather than showing a deserved deference, to our kingdom companions.

Secondly, take on the challenge of cutting red meat out of your diet, even if for just a week. Red meat generally includes beef, but if you’re up for the challenge, ban pork from your diet as well. You might just find yourself surprised at how easy it can be to eat only chicken and fish. On the other hand, try meats from animals outside of the primary realm of the American diet: goat, duck, rabbit, jellyfish, snails, insects, and more. The realization that there is more to meat than beef, pork, chicken, and fish, is an important life lesson.

Finally, while giving up meat may mean giving up some of your favorite dishes and being forced to watch other people devour them, it is often beneficial to look at it this a practice of self-control rather than sacrifice. The practice of moderation can be extended to all other areas of life. You must aim to perceive the practice of vegetarianism not as giving up meat, but as exploring other forms of protein and experimenting with the limits of nutrition.

Admittedly, I made the decision to quit meat only a year and a half ago, but I have not regretted my choice once since. I regard it not only as one my largest contributions to the Earth as one of her citizens, but also a long term experiment with self control and thus a test of psychological stamina. I believe it is an ever-evolving journey, one in which I aspire to see eye-to-eye with my food.

6. An Absolvement from Meat

A few seconds of reflection before we dine is all it takes.

I distinctly remember my last steak. It was a sweltering summer day in Florence and the region’s specialty: a hefty and sensational steak. I had already begun to limit myself to white meat, but I figured that I should experience a Florentine steak at least once in my life. Why not? And yet I used this same ideology when I became a vegetarian. Why not? It almost seemed too simple. As with most choices in our lives, it was a decision between yes or no, will or won’t. Should I eat an apple or an orange? Should I bike or drive? Should I go my own way or should I follow the crowd? It is a churning deep within the pit of my stomach that determines the outcome of these choices. It steers me and my life towards new challenges and draws up new aspirations. It pushes and pulls me: towards certain choices, and away from others. It forces me to question, examine, contemplate, and discover the world around me and to never surrender my spirit of curiosity. Nevertheless, whichever path it tells me to travel down, it is a decision that I rarely regret.

With my own resolution, I challenge you to attempt the endeavor, even if it may only be for a few days. Attempt to intertwine yourself with your food: question it, examine it, contemplate it, prod it, nibble it, and discover it. By this article, I do not mean to guilt or pressure anyone into make significant changes to their diet. My intention is quite the opposite: I hope to inform the reader about the widespread effects of our everyday sustenance and to convince readers to simply contemplate the origins of their food. A few seconds of reflection before we dine is all it takes. Why not?

Further Reading:

World Health Organization, Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases

Worldwatch Institute, Global Meat Production and Consumption Continue to Rise

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Meat consumption

National Geographic, What the World Eats