*I will be using the gender-neutral pronoun “they” since Kawashima’s gender identity is unknown.

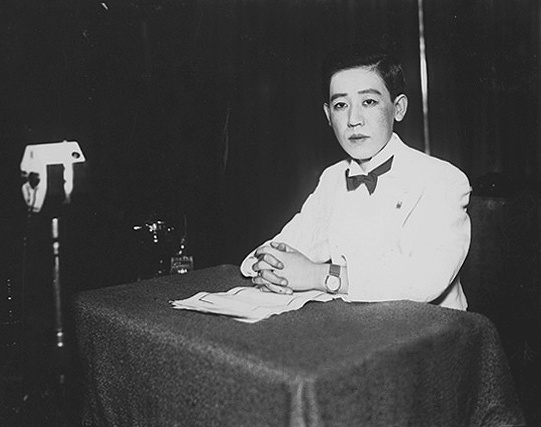

Here’s somebody you won’t learn about in history class. *Yoshiko Kawashima. Chinese traitor, Japanese commander and the genderqueer bisexual legend we all deserve.

Originally named Xianyu, Kawashima was born a Beijing princess in 1907. It wasn’t until they were eight when revolution forced them to become adopted by a Japanese Mercenary. It was then that they were given the name that would rock history. Yoshiko Kawashima.

Kawashima was flamboyant and energetic, Japan’s own teenage Casanova. On top of riding a horse to school every day when most would walk or drive, they practiced Judo and was very talented at Kendo (a sport similar to fencing). Despite excelling both in sports and the social sciences, Kawashima was expelled due to unruly behavior.

However, Kawashima’s life was far from perfect. Their foster father openly harassed them and often bragged about marrying Kawashima to his friends. He would act violently if he saw them so much as smile at another man. He raped Kawashima when they were 17.

Kawashima spiraled into mental illness, going as far as attempting suicide. It became clear to them that they must leave home, to make their life their own.

So Kawashima dived into the cities. They cut their hair and started wearing boy’s clothing, shocking both the public and the press. “People criticize me and say that I am perverted, and maybe they’re right,” Kawashima said in a Japanese newspaper, in 1925. Cutting your hair when born a woman was unheard of in conservative Japan. The public nearly fainted when Kawashima said they “decided to cease being a woman forever” and that they had “a tendency toward the third sex.”

Kawashima was not fazed by what others thought. It wasn’t long until Kawashima started their collection of rich lovers men and women with nothing more than charm and good looks. “That’s my wife!” Kawashima would brag, pointing at their newest mistress, smile oozing with confidence. Their new life of bohemian luxury and carelessness was soon to be interrupted.

Two years later, China remembered the Beijing princess once named Xianyu. Kawashima was forced to move into Mongolia, married to a Mongolian prince. A politically convenient union created by their stepfather and the Chinese government. Long story short, Kawashima’s royal connections didn’t last long; Kawashima divorced the prince and promptly moved to China.

Despite divorcing royalty, this wasn’t the end of Kawashima’s political career. They soon found themselves a Japanese spy in one of the most monumental Asian wars of all time, the attempted Japanese invasion of China, aka the second Sino-Japanese war. As a spy, they used their fearlessness and notorious glamour to seduce Chinese officials in shady Shanghainese bars, manipulating them to provide useful information to the Japanese.

Kawashima would again use their manipulation skills to exploit their cousin Puyi, a child emperor, to become emperor of the new state Manchukuo (previously known as Manchuria). There, Kawashima organized their own militia of over a thousand men for the Japanese state. As Commander Jin, Kawashima became a celebrity; many called them the Joan of Arc of Manchukuo. They even released a record of their music and starred novels, the people star-struck by their very presence. However, their popularity was their downfall.

Kawashima’s military experiences are hazy. The reason? They were so popular that authors began to write about their supposed military conquests— that never happened. And with Kawashima’s prideful nature to claim glory whenever they could, the line between fact and fiction continues to blur.

Kawashima’s military experiences are hazy. The reason? They were so popular that authors began to write about their supposed military conquests— that never happened. And with Kawashima’s prideful nature to claim glory whenever they could, the line between fact and fiction continues to blur.

It didn’t help that Kawashima’s loyalties didn’t lie with only the Japanese. Once they saw how cruel the Japanese treatment was of the native Chinese people, they immediately began to protest. These actions caused them to be cast aside by both China and Japan. They fled back to China, narrowly escaping an assassination attempt. They were able to open a quiet restaurant near Shanghai and live peacefully with four pet monkeys, but were later arrested by the victorious Chinese (who had help from foreign allies) for the treasonous military acts in the novels and movies about them.

They claimed that Kawashima was Chinese and worked for the Japanese, and therefore was a traitor. Although Kawashima argued that they were technically a Japanese citizen, this did little to change the Chinese government’s opinion. In 1948, Kawashima was publicly executed at the age of 41. In their pocket was a poem they had allegedly read to themselves since childhood.

Though there is a home, I can’t return

Though I am in tears, I don’t know how to express in words

Though there is a low, it is not righteous

Though there is a false accusation, to whom I can appeal?

This poem eloquently describes the hardships of Kawashima’s life of feeling divided between countries, between gender roles, and between morals. But even after their death, they remained as powerful as they were when they were alive. For decades, there were rumors that Kawashima was still alive, and that the execution was fake. Kawashima’s legacy continued in the East as books, movies, soap operas, and even video games. The excitement and mystery of Kawashima’s life still captivates people today, their story of survival and adventure deserved to be shared all around the world.

This is part of a (roughly) monthly column highlighting Astounding Asians that we don’t learn in history class! If you have any questions or suggestions, please contact Michaela Seah at [email protected].