Since 1948, South Korean law has mandated all able-bodied male citizens between 18 and 35 to serve in the military for 18 to 24 months. Enacted in the years where a North Korean attack was a persistent threat, the policy was made out of fear for national security. But even as decades have passed since the mandate’s establishment, conscription has remained just as uncompromising as it was in the 1940s – and becoming a topic of controversy in the process.

That’s because the world has changed, and South Korea is far from being the vulnerable country it was back when conscription was introduced. The country is maintaining a defensive alliance with the United States and has military reserves far larger than their northern neighbors.

Coupled with the North Korean threat becoming primarily nuclear, reducing the effectiveness of a standing army, some are being questioning whether the requirement is truly necessary.

Furthermore, the South Korean military is notorious for rampant abuse and its extremely toxic environment. Cases of abuse are reported almost regularly, and mental health resources are held to a minimal standard, the consequences of which are clear. A 2023 investigation found that as many as 13,000 self-inflicted deaths were directly linked to South Korean military service, adding to the total of 74,674 non-combat deaths reported since 1948. No living person deserves abuse on this level – and least of all the group of people who are subjected to mandatory service, who are most often out of high school or just barely legal adults.

Still, many South Korean citizens would probably agree that the mandatory service requirement is valuable – in fact, according to a 2021 Gallup poll, 42% of South Koreans thought that it should remain as-is, due to the northern threat and perceived societal benefit from service. But what about when people who have religious reservations, like pacifist groups who have beliefs actively against violence? For these groups, or anyone else unwilling to serve, South Korea has a solution — sending them to prison.

These people perform alternative services within prison for three years, even eating and sleeping there. This is longer than any other alternative civilian service in the world, and twice as long as the old alternative which was just prison (often 18 months) and a criminal charge. People are taken from their everyday lives for years, detained for their beliefs against violence and fighting.

To most people living in the US, global problems like these seem mostly irrelevant – and here at Palo Alto High School, surrounded by the Silicon Valley bubble, it’s even easier to ignore the issues that aren’t directly in front of us. However, the South Korean conscription dilemma isn’t a distant issue – it’s one that an estimated two million people of Korean descent living in the United States must face. And even in the Paly bubble, it’s a reality that every Korean-American student with dual citizenship has to confront on the daily.

That’s because the mandate doesn’t just apply to residents of South Korea – it applies to anyone with a South Korean citizenship, including those with residency in the United States. People living an ocean away from South Korea are still forced into spending three years in military training for a country they don’t even live in, regardless of their circumstances.

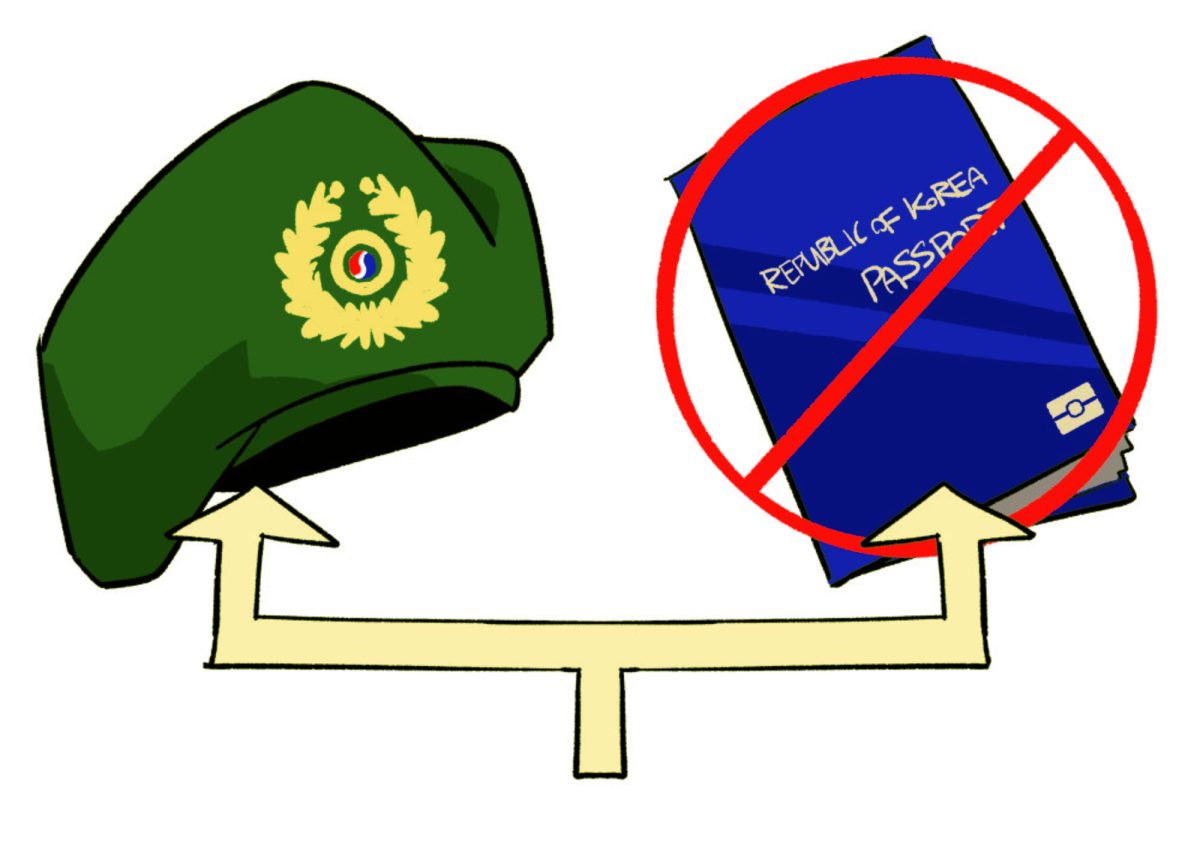

A common solution to avoid service is renouncing citizenship – but this solution is far from being ideal. For one, South Korea makes this choice irreversible after the decision is made – according to Article 9 of South Korea’s Nationality Act, someone who loses or renounces their citizenship to avoid conscription cannot regain nationality, meaning that achieving permanent residency and receiving any kind of Korean governmental aid is impossible.

Another problem then arises for people living in the US temporarily. Although we all have our grievances with the College Board, the Korean education system is somehow even more unforgiving – the university that students are admitted into is based purely on the results of a single test, administered once a year on a national scale, with no retakes, redos, or make-ups. If you’re sick on test day, or have a family emergency, South Korea tells you to try again next year and repeat the grade.

As a result, many students come to the United States for their education before returning back to the mainland – however, it doesn’t take long before they run into the conscription dilemma. The South Korean government mandates that out-of-country residents with multiple citizenships at age 20 must choose one or the other before turning 22, with the same penalty of irreversibility.

This leaves Korean-Americans between a rock and a hard place when it comes to service – they can either choose to give up foundational years of their life to a system they’re barely involved in, or give up their South Korean citizenship. And although renouncing citizenship isn’t a big deal for everyone, the fact is that the United States isn’t always a place of permanent residence for Korean migrants – and for this group of people, the result is disastrous.

For Paly students facing this dilemma, or for any other Korean dual citizen across the United States, the choice ultimately becomes one between their nationality and their freedom — and one that has to be made imminently, or the choice is made for them. The rigidity is the key issue, and if addressed could make the issue significantly less extreme.

There are much more effective ways to implement alternative civilian services that prison – and many countries do. In Austria, the government offers Zivildienst as an alternative to its mandatory conscription which is nine months compared to the regular military service’s six, and participants help out in every sector from nursing homes to rescue. Rather than putting objectors into prison to work, South Korea would benefit greatly from allowing them to work in hospitals and the like instead.

Allowing a longer term to make the citizenship decision for out-of-country residents could address the issue with out-of-country dual citizens as well – would allow these people time to choose or finish their education, and alleviate the significant pressure that young people face in their foundational years to an extent where decisions could be informed and thought through. Considering the persistent threat of their northern neighbors, it’s a tough ask for South Korea to eliminate mandatory conscription – but at the very least, South Korea should improve alternatives and add further flexibility to service, so that the burden of this choice isn’t on the shoulders of people who are – whether residents or not – frequently below the legal drinking age.

South Korean military conscription is deeply traumatic for many who undergo it – and oftentimes, deadly in some cases, and is losing popularity among its people. The government forces dual citizens to choose to either renounce citizenship forever or to maintain their South Korean citizenship and be conscripted if eligible.